I went in search of my family roots in Slovenia and met a self-proclaimed knight who could be a distant cousin.

“You are home.”

The man in the fur hat expansively waved his hand at a hillside where the ruins of a 1,000-year-old castle could be seen, partially covered by tree branches. I came to this hidden corner of Slovenia to meet some of the people who share my family’s last name. By the end of the day I would discover that we shared much more.

Meet the Anžur Family from Central Slovenia

Let’s go back and begin with the part of the story that I know:

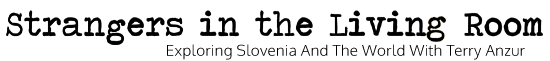

My grandfather, Johann Anžur, was born in the farming hamlet of Goliše and baptized in 1876 in the nearby parish church of Kresnice, a tiny farming community on the Sava River in Central Slovenia. He served in the Austrian Army and married a local girl, Franciska Mohar, born in 1882. Johann and his brother-in-law, Franc Mohar, were the first to go to America in 1904. Ellis Island records support a family legend that Johann had to go to America twice; apparently going back to Europe and then entering the US again in 1910. Franca followed in 1911 with their three children, Johann, age 8; August, age 7; and Paulina, age 6. They departed Europe on the S.S. Lapland from Antwerp, Belgium.

The Anžur family posed for this portrait in Ljubljana before they left for America.

Before they left, the family posed for a photograph in Ljubljana. The picture is carefully composed like a classic oil painting: the oldest boy holds a model ship as the family prepares to sail to a new life; the father places his hand on the shoulder of the second son, who proudly grips a toy rifle; the mother holds on to her daughter with one hand, the other holding a bunch of flowers in her lap. Her feet rest on what looks to be a suitcase. They appear well dressed and hopeful, not desperate or poor. So why did they leave? Probably, I’ll never really know.

Sometime after they arrived at Ellis Island, the family adopted the Americanized pronunciation and spelling of their last name: Anzur. They settled in Shamokin, Pennsylvania, where my grandfather worked as a coal miner and hand-built them a modest home. My Aunt Libby and my father, Ed Anzur, were born there. My grandfather died when my dad was 3. Family lore has it that he fell into a snowbank on the way home from the mine — whether because of a heart attack, foul play or excessive drinking is uncertain — and froze to death.

This left my grandmother in the care of her two oldest sons, my uncles who helped to raise my father. Wanting to leave behind the old world and fit into the new one, they did not permit my dad to learn German or Slovene language. My grandmother lived to see my dad serve in the Navy and graduate from Villanova University. She died of stomach cancer before my parents married and I was born. My uncles, now known as John and Gus, either didn’t remember their early childhood or didn’t want to talk to me about it. I don’t recall ever meeting Pauline; her fate remains something of a mystery. I grew up under the impression that we were somehow Austrian, because my grandfather had served in the army of Emperor Franz Josef. It never felt right.

My grandmother left behind a brother in Kresnice. Uncle Tony (Anton Mohar) sent postcards written in a native Slovene dialect, telling of his life as a tailor. After World War II, he fell on hard times in what was now Yugoslavia. My family sent him aid packages of clothing and shoes through the Red Cross. He and his wife, Julija, moved to Litija as new factories in the area created more work opportunities. By the time my brother John and I began researching our roots in the 1970s, Uncle Tony had died and Julija’s grown children didn’t have any information on the Anžur-Mohar side of the family. They did, however, have baby pictures of me and my brothers that had come with the care packages. Still, it never felt right to say we were Yugoslavian.

On my first visit to Kresnice in 2009 with my own husband and son, I wandered through the graveyard at the village church on a rainy spring day. Struck by the beauty of this green river valley but too timid to knock on any doors, I feared the search for my family roots in Slovenia had reached a dead end.

Our Facebook Cousin: Tanja Anžur

I wasn’t the only person curious about my last name. A Slovene woman named Tanja Anžur contacted me on Facebook, after her Google search had turned up information on me and my TV career in the United States. As I started to spend more time in Ljubljana in 2016, we met and became friends. We couldn’t turn up any common ancestry, except that our families were from the same general area. There was, however, a physical resemblance. When our Facebook cousin stood next to my son, they could have been mistaken for brother and sister.

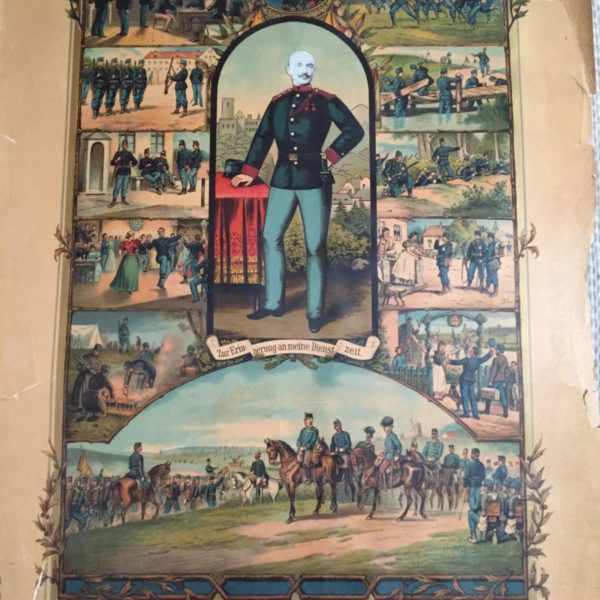

The next clue came from Igor Evgen Bergant, the RTV journalist who interviewed me on the Odmevi program. He sent me a link to the craft brewery Volk Turjaski, run by a man named Vitez Matjaž Anžur. “He’s a self-proclaimed knight,” said Bergant, explaining that “Vitez” was the Slovene designation for a knighthood, translating to “Sir” in English. “Don’t be surprised if he has traced your last name back to the Slavic pagan times.” The TV host was quick to dash any hope that I might be the descendant of a Slavic warrior princess. More likely, he assured me, I would find a bunch of boring farmers in the family tree.

Meeting a Slavic Knight: Matjaž Anžur

Meeting the Slavic knight would be anything but boring. He responded to my email right away, inviting me and my son, Andrew, for a visit: “When I saw you on TV, I said, ‘That is my relative!'”

Searching for clues to my family roots.

He met us on a warm, sunny winter day outside our apartment in Ljubljana. It was hard to miss the striking figure in the fur hat. A friend’s car was parked a short distance away. Tanja came along to help with the translations as we spoke in a mix of English and Slovene. Proud of his Slavic ancestry and pagan beliefs, Matjaž has written several history books. Along with his three sons, he participates in costumed re-enactments of local events.

He did, indeed, have some thoughts on the origin of the Anžur name. “It is derivated from ANŽE, what is still today a very common first name in Slovenia, after the Etruscan god, Janus. The sufix UR means in slovenian language “big” or “not quite good”. It probably refers to the descendants of some ancient fighter — one named Anže.” So my Slavic ancestor was a dude known as “Big Bad Anže”? Cool!

Matjaž welcomed us into his home, on a rolling hillside near the ruined castle of Šentjurjeva Gora. We shared pictures of my family and I learned a little more about his: on his mother’s side he is related to the noblity associated with Turjak Castle. That’s where the brewery name “Volk Turjaski” — wolf of Turjak — comes from. We tried four different varieties of his craft beer, all delicious.

Food History: Potica and Goveja Juha

A short distance away, we were welcomed to Sunday dinner by 82-year-old Stefania, Matjaž’s mother. Key to this unforgettable meal is the word “domača” — homemade, beginning with a toast of strawberry liquor.

I recognized many of the traditional Slovenian dishes I enjoyed while growing up, including goveja juha (beef soup) and potica for dessert. And plenty of homemade cviček, a low-alcohol Slovenian mix of red and white wine. I’ve had these same dishes cooked by TV chefs in fancy Slovene restaurants, but food is always better when it is made with love by a “babica.” Having never known my own Slovene grandmother, I was in tears by the time we exchanged hugs.

Having never met my own Slovene grandmother, I will treasure this hug from the matriarch of a family who shares my Slovenian surname.

Then, it was back on the road to Trebanjski Vrh, another tiny farming settlement (population 43). Along the way, Matjaž pointed out houses that had some connection to the family. We pulled over to meet another possible cousin, Darko Anžur. In the graveyard surrounding the Church of St. Jernej, Matjaž pulled back the bushes to reveal the grave of a possible common ancestor: Janez Anžur, born in 1859.

We finished the evening with one of Matjaž’s uncles. Eighty-five year old Stanislav Anžur and his charming wife Justina insisted we drink more homemade cviček and taste homemade pršut as we discussed our family tree. It will take more research to determine the exact connections, but one similarity was unmistakable. Stanislav looked at me with the same brilliant blue eyes as my Slovene-American father, Ed Anzur.

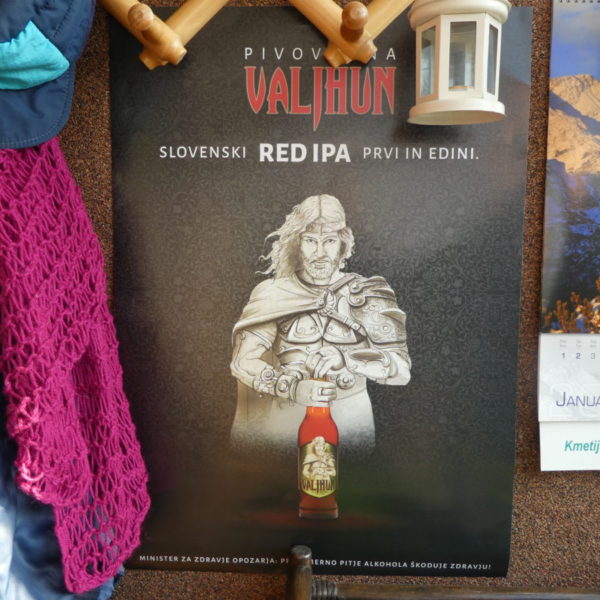

Finding Your Ancestors in Slovenia

When my son and I applied for our Slovene citizenship though ancestry, we hired a lawyer to locate my grandfather’s baptism certificate (Kristni List in Slovene). My grandmother’s baptism certificate could not be found. However, Ellis Island immigration records were extremely helpful in establishing my dad’s family as ethnic Slovenes from what was then Austria. Ellis Island and census data up to 1940 in the US are theoretically free to access, but you might have to sign up for a “free trial” of ancestry.com which eventually becomes a paid membership unless you cancel it.

The Slovene Statistical Office keeps track of the different family names, officially counting 240 people with the “priimek” of Anžur in the nation. It is searchable in English. I was lucky in finding Matjaž, who has experience in researching Slavic history. He also has some relatives in Cleveland, Ohio, and asked for my help in tracking them. So we have a lot of work to do!

And yeah, I’m going with Slavic warrior princess.

Terry’s Travel Tips

Take your time: Don’t make the mistake that I did in 2009! Armed with only the name of my grandparents’ hometown, I planned just one day in Slovenia to “find my roots.” This is a process that takes more time, especially if the nearest possible known relatives in Slovenia have died and you are looking for more distant cousins.

The Dark Side: In addition to centuries of battling invaders and being ruled by outsiders, Slovenes endured some difficult history in the 20th century. Some of the most brutal fighting in World War I was on what is now Slovenia’s territory. Then, Slovenes were caught between Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in World War II, with Communist partisans emerging victorious to create post-war Yugoslavia. Slovenia emerged as its own country just before the painful Balkan war of the early 1990s. Don’t be surprised if a conversation about family history includes people on various sides who were lined up against a wall and executed.

Bring Gifts: I was overwhelmed by the hospitality of the Anžurs still near Kresnice. Plan to bring gifts for the host/hostess if you think you will be invited to their home. They insisted on gifting me with a bottle of the homemade cviček and a package of potica. Next time I won’t arrive empty-handed!

Read More: Finally, if you’d enjoy a historical fantasy novel based on Slovenian history and legends, please check out my son ‘s books on Amazon. He’s a Slovenian American author living in Ljubljana. His books — Keepers of the Stone and Voyages of Fortune — feature a character who was born in America but travels through time to discover his Slovene roots. Available in both print and ebook versions. Thanks in advance for leaving a review on Amazon or Goodreads.

Book Update: Andrew has since published Tito’s Lost Children, an alternate history of the breakup of Yugoslavia. Book One focuses on a fictional group of teenagers caught up in the real events surrounding Slovenia’s 10-day war for independence. One of the characters, Antonija Mohar, was inspired by our real-life Slovene ancestors. Andrew is a PhD who bases his stories on solid historical and political science research about the former Yugoslavia.

Visiting Slovenia to Find Your Roots: It’s a small country, so wherever your family came from is likely to be less than a two-hour drive away from the capital city, Ljubljana. Thanks for browsing the hotel reviews and booking on Trip Advisor to support this blog at no cost to you.

Want more insider tips on finding your roots in Slovenia? Like @strangersinthelivingroom on Facebook, and sign up for the occasional email when there is a new post here on the blog.

Author Andrew Anzur Clement, searching for his ancestry and new stories in the archives of the Roman Catholic Church in Ljubljana.