After more than a decade of searching for my ancestors in Slovenia, I found help in a most unexpected place: Facebook.

In this post, I’ll share what I’ve learned about starting in your home country and then researching historical records in Slovenia. You might also need a bit of luck and the kindness of strangers to trace the roots and branches of your family tree:

- Slovenian Genealogy Facebook Group

- How to Start Researching Your Slovenian Ancestry

- Does DNA Testing Help?

- Lost in Translation: The Curse of Cursive Handwriting

- Roman Catholic Church Archives Online and in Slovenia

Slovenian Genealogy Facebook Group

If you are just getting started on your Slovene ancestry search, you should join the Slovenian Genealogy Facebook group . It has more than 5,000 members. You must answer three questions in order to be admitted, with details of your interest in finding your Slovene roots.

Once you’re in the group, a good place to start is by clicking on the tab called “files.” You’ll find posts on everything from travel tips to recipes, plus this Slovene ancestry Q and A to get you started. You can save time by using the “search this group” box for specific topics. You might find someone else has already researched your family surname or hometown. You’ll also find translations for words like “hübler” that turn up in the old records.

Mary Urban administers the Facebook group in the US. She’s the granddaughter of Slovene immigrants who settled in Waukegan, Illinois. She started what is now the Facebook group in 2000 to display photos found in an old box in Mother of God Church in Waukegan, Illinois. Her advice: “Start in the USA (or other home country). If you can’t find specific names, dates and places of birth (even parents’ names) don’t bother trying to do research in Slovenia. Be prepared to spend time and money and be patient.”

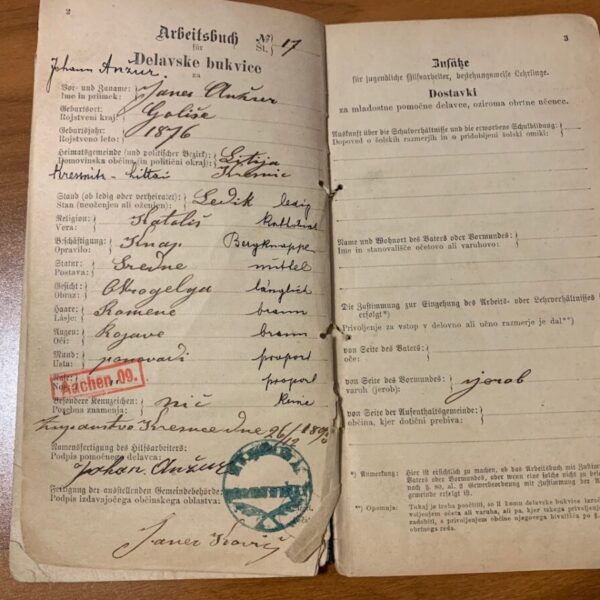

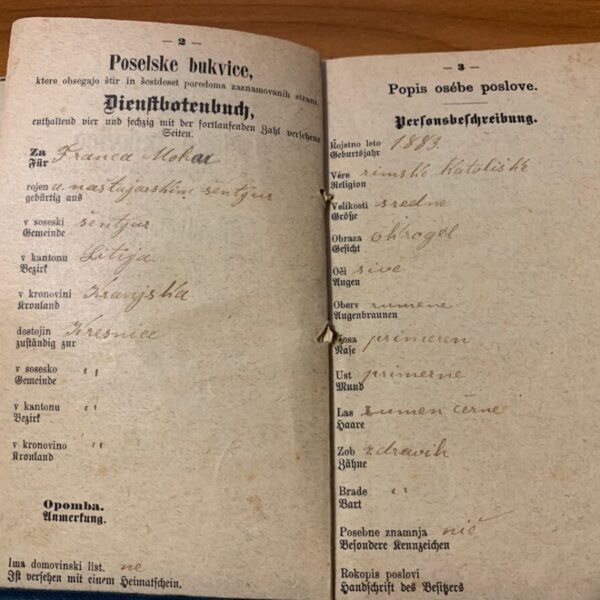

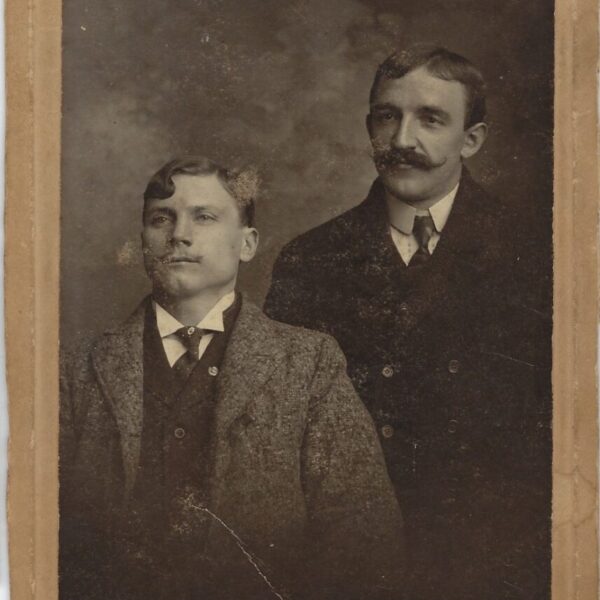

Here’s a gallery of the “old things from Dad’s family” that I rescued from a box my mom was about to toss in the trash. Click on each image for a caption.

How to Start Researching Your Slovene Family Tree

- Elderly Relatives: Talking to your older family members can provide useful clues, but might also result in stories that turn out to be embellished folklore. Be sensitive but persistent if they are reluctant to talk about the often painful reasons why they left. And don’t wait; I regret not talking more with my older relatives who were born in the Old Country, before they passed away.

- Old Photographs: Fun to look at, but they’re mostly useless unless you know who’s in the picture or where and when it was taken. What’s written on the back of the photo might be more useful than the image.

- Family Records: Mary Urban advises grabbing onto every old document, letter or postcard that you find in your grandparents’ attic or other family archives. “Be careful what you consider junk and throw away,” she adds. “Be prepared to make phone calls and travel to cemeteries, churches and government offices.”

- Online Searches: Mary also recommends a paid subscription to Ancestry.com, although I’ve used mostly free resources like Family Search, the genealogy site operated by the Mormon Church. Check Find a Grave and Slovene-American newspaper archives. Again, the Facebook group can be helpful.

- Census Records: In the United States, US census records provide statistical snapshots of where families were living and who were the members of the household, their birthplaces, ethnicity, occupations and their ages in a given year. You can search the US census records for free. The census must have been taken more than 72 years ago before it becomes available to the public.

- Immigration Records: A free search of Ellis Island immigration records can help you connect your immigrant ancestors to the places they came from, the name and address of their closest relative back home or a contact at their destination in America. You might even learn the amount of money under $50 they had in their pockets when they arrived.

This picture shows the Anzur and Mohar immigrants from Slovenia on their front porch in Shamokin, PA shortly after they were reunited in 1911. But now they had different names! In the front row is my grandmother Frančiška, who became Frances. Her brother Franc Mohar, top left, became Francis Macher and my grandfather, Johann Anžur, top right, was now John Anzur. The kids are my Aunt Pauline and my Uncles John and Gus. I’m guessing the woman next to Uncle Frank is his wife.

How did they spell their Slovenian name? You might be lucky and get an exact match by typing in the names of ancestors you know about. However, Slavic names were often misspelled by the immigration clerks or changed later to sound more “American.” You might need a little more information to find them in the church records in Slovenia or in the Ellis Island arrivals. If you know the correct spelling of their last name in Slovenian, you can check the website of the Slovenian government statistical office to find out how many people have that name in Slovenia today, and in what parts of the country it is most common.

WHEN did they leave? You should also take note of WHEN your ancestors left what is now Slovenia. Ellis Island records and available census data are helpful for tracking the huge wave of immigration in the late 1800s and early 1900s. An individual’s birthplace can be listed as Austria or Yugoslavia but they could be identified as ethnically Slovene.

Post-World War II Immigration: There is a separate Facebook Group for those researching families who left what is now Slovenia during or after World War II. This was a dark period of history that remains divisive in Slovenia to this day, as new details of postwar persecution become available.

Project Ancestry for Displaced Persons: If your ancestors were among the estimated 100,000 Slovenes who fled to Argentina, Canada, the US or Australia between 1945 and 1970, you should check out the genealogy resources on Project Ancestry. In addition to camp records, articles, links and videos, they are collecting stories of Slovenes and other displaced persons who spent time in postwar DP camps while waiting for a new country to accept them as immigrants. This website, based in Austria, was started by an Austrian of Slovene/Croatian descent and his Australian wife; it is not part of Ancestry.com.

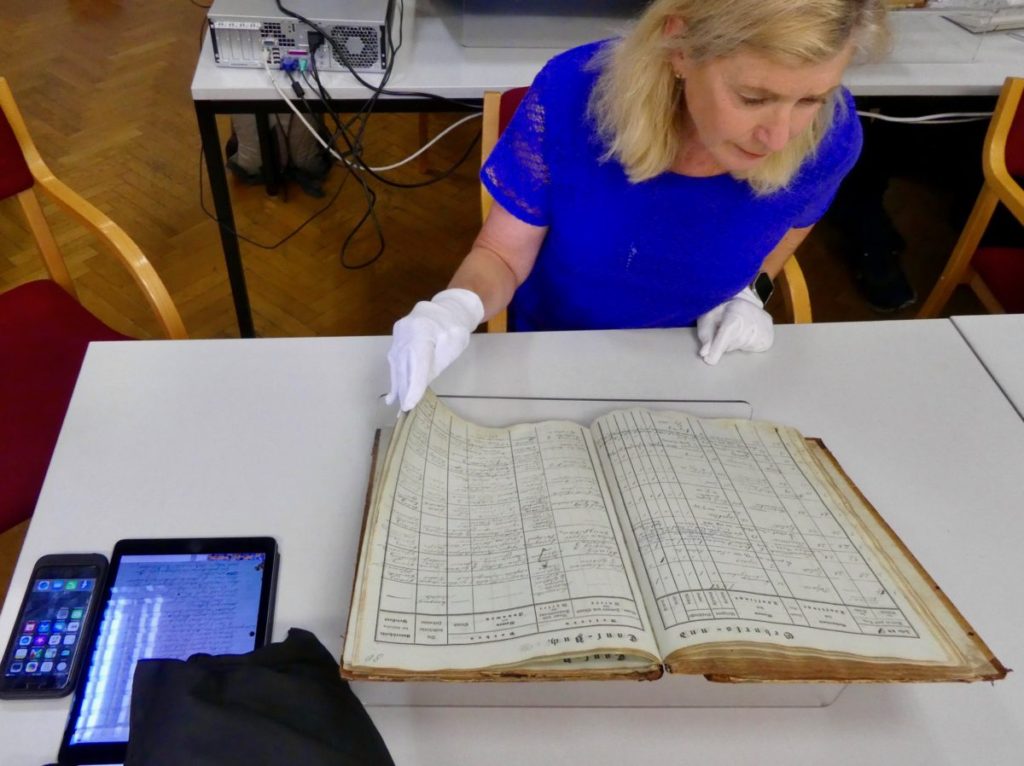

It took some detective work to track down this 1904 record of my grandfather, Johann Anzur, arriving at Ellis Island with his brother-in-law Franc Mohar. On lines 14 and 15 they are listed as Slovenian, but whoever transcribed this for the website mistakenly wrote “Slovak,” so they did not come up in search engines.

Lost in Translation: The Curse of Cursive Handwriting

If you’ve followed the above advice to start with your own family records in the USA and immigration/census archives, you might be struggling to decipher old documents about your Slovene ancestors. You’re not the only one who has trouble with cursive handwriting. It took me years to confirm a family story that my grandfather came to the USA twice. He first arrived with my great uncle Frank (his brother-in-law) in 1904, but the person converting the ship’s manifest into text for the website mistakenly translated “Slovenian” in cursive on the original record to “Slovak.” The birthdates, occupations as miners headed for Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, and the name of my grandmother — left behind in Kresnice with two kids and pregnant with a third — confirmed I had the right people. My grandfather’s arrival is recorded a second time in 1910, indicating he must have left the US and returned before my grandmother and their kids arrived in 1911.

Family correspondence may be in a dialect of German or Slovene and written in a cursive script. Many church notations are in Latin. The handwriting can be either really good or really bad. Whether your ancestors were praised for their fancy penmanship or barely literate, you most likely need an expert to decipher it today. That’s where the Facebook group comes in. Among the members are native speakers and genealogy enthusiasts who can actually read the archaic handwriting and will kindly do a quick translation if you post a picture of the document. Be sure to say THANK YOU to these volunteers for their time and expertise.

Pro tip: Post a separate picture to the Facebook group for each page you’d like translated.

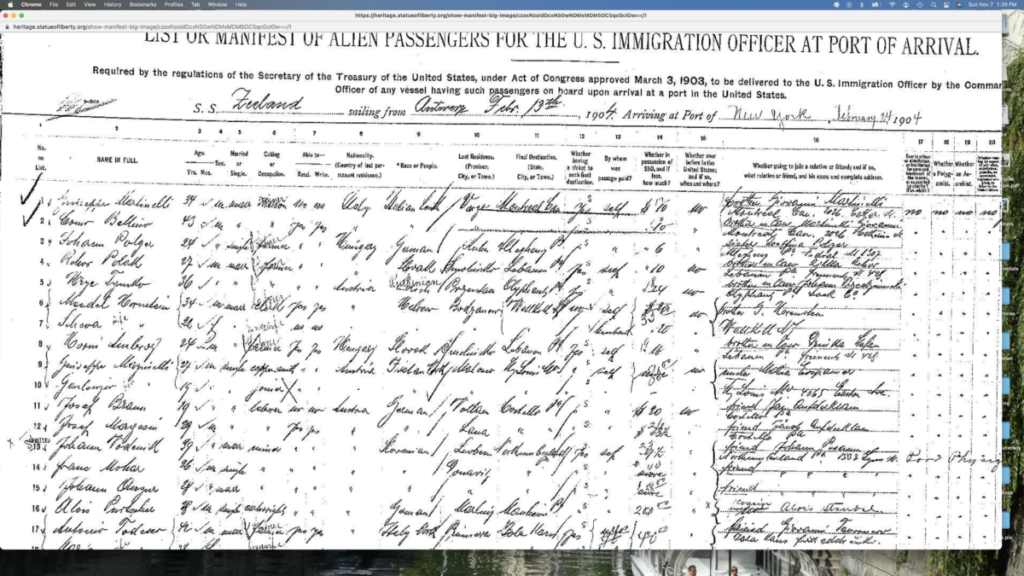

The Facebook genealogy group connected me with Tina, who kindly offered to decipher my ancestors’ cursive handwriting in Slovene dialect. Here, she is translating a postcard from a great aunt I didn’t know I had — in Kansas!

Tina Petek Steinbücher helps administer the Facebook group in Slovenia. When I met her in Ljubljana she kindly looked through some of my family’s correspondence. She cleared up a mystery about my grandfather’s middle name, Decoll, which didn’t sound Slovene or even Austrian. It turned out to be a Latin reference to the beheaded John the Baptist, apparently my grandfather’s patron saint.

Amidst the routine birthday and holiday greetings, I learned that my grandmother, Frančiška Anžur (maiden name, Mohar), had a lot on her mind while waiting for her coal-miner husband to save up enough money to bring her and their three small kids to Pennsylvania in 1911. “I am writing you from here for the last time,” she wrote from her home town of Kresnice after packing their bags and buying a ticket to depart Europe from Antwerp, Belgium. “I worry a lot about the school for the children.” She also received news from her sister, Julija Mohar, who had emigrated to Frontenac, Kansas in 1907: “My husband works two jobs. My married name is Zupančič and that is how you can find me.”

Unfortunately, Great Aunt Julija’s story doesn’t have a happy ending. The Facebook group unearthed a Kansas newspaper story on her divorce in 1918, alleging extreme cruelty, habitual drunkenness, frequent beatings and threats to kill. That same year, she visited her sister (my grandma) in Shamokin, Pennsylvania during the flu epidemic before returning to Pittsburgh, Kansas. In 1924 she penned a heartbreaking letter to the newspaper, reacting to the story of another abused wife and the hard times the miners’ families endured. In 1928, her ex-husband committed suicide, “driven to his death by his sad situation.” US census data indicates they had no children. A court denied Julija’s claim to Anton’s SNPJ insurance death benefits and she later remarried. Still, her first husband’s gravestone in Frontenac leaves a blank space for the death year of “Julia, my wife.”

Lesson learned: the story of your Slovenian immigrant relatives, and those who endured two world wars in their home country, might not be a “fairytale.”

Does DNA Testing Help?

You might have considered using a DNA testing service like 23andMe or AncestryDNA to connect with your roots. But before you fork over your money and your spit, be aware of the privacy concerns. You’ll need to sign over permission for testing companies to sell your data to pharmaceutical companies or share it with law enforcement.

Tina Petek Steinbucher points out that DNA testing is not widely popular in Slovenia, so you might have dozens of hits from people in the United States who are descended from immigrants, but none in the area that is now Slovenia.

Mary Urban says her pet peeve is “people who throw around their (DNA) numbers without researching.” She cites examples where official records might reveal an adoption or illegitimate birth that puts a quirky branch on your family tree. And once you get beyond a generation or two, she says, distant cousins may not share much DNA at all.

Another researcher told me that DNA information is sometimes distorted by Slovenia’s history as a crossroads of trade routes. “Since Roman times all the traffic went through here,” she points out. “Based on your DNA alone you can’t say, ‘I’m Slovene.'” You are more likely to get on the right track by following the dusty paper trail your ancestors left behind.

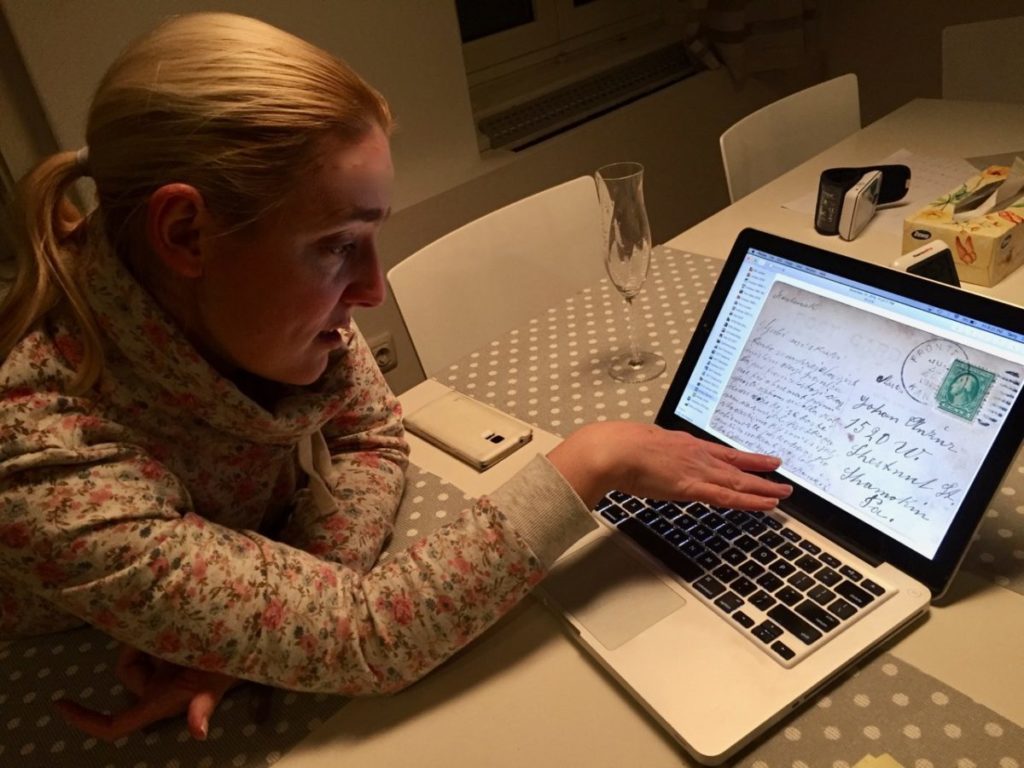

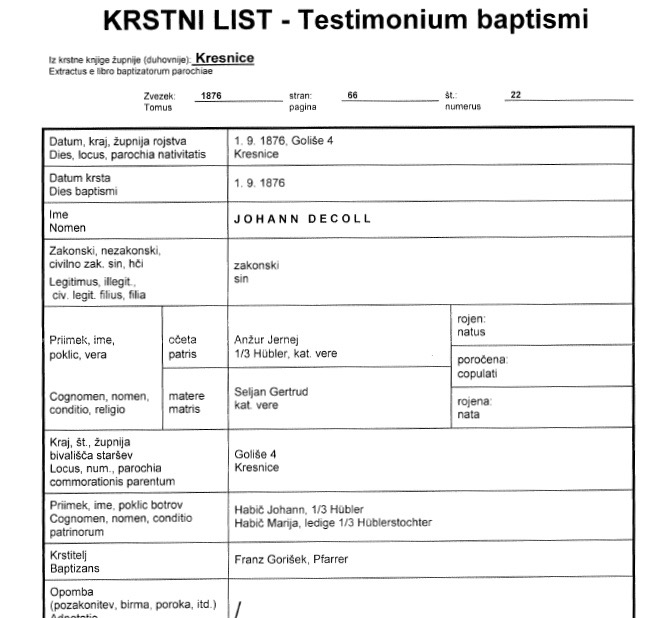

On Line 22 of this book from St. Benedict’s Church in Kresnice, the handwritten record of my grandfather Johann Decoll Anžur’s baptism as it appears in the archives of the Archdiocese of Ljubljana.

Finding Genealogy Records in Slovenia

“The main thing for someone from the US who wants to do research in Slovenia is preparation,” Tina Petek Steinbucher explains. Once you have the names, birthplaces and approximate birthdates of the people you are looking for, you are more prepared to start looking for your family roots in Slovenia. Locating the city, town or village will help you find the church that kept records of your family and connect with its book at the local parish or in the diocesan archives.

This might be a good time for a quick introduction to Slovene place names. There are many places named Dol or “Dolina” (valley) or “Gora” (mountain) so it helps to specify the nearest large town with pri (near) and the name of the town. For example, the tiny village of Kresnice and an even smaller place called Golišče are the hometowns of my Mohar and Anžur ancestors, but the largest nearby city is Litija. Saint Benedict’s is the parish church in Kresnice.

Local priests recorded baptisms, which were usually performed on the day of the baby’s birth because of a high risk of infant mortality. The document called a “krstni list” is the closest thing your ancestor had to a birth certificate, and it’s something you’ll need if you are trying to claim Slovene citizenship through ancestry. It should also give you the names of the person’s parents and their occupations.

The transcription of my grandfather’s baptism record from the Archdiocese of Ljubljana archives shows the names of his parents and what they did for a living — in German, the language of the Austrian empire. In this case, farming.

Online Genealogy Records from the Archives of the Roman Catholic Church

The Ljubljana Archdiocese archive is just one of three in Slovenia. If your ancestors were Roman Catholics from Central Slovenia, you’re looking in the right place. The church has other archives in Maribor (East) and Koper (West). Records from Ljubljana and Maribor have been posted on a website called Matricula Online. No word on when Koper might be added. There are separate books for births, marriages and deaths. Project Ancestry offers this helpful tutorial with a video on how to search.

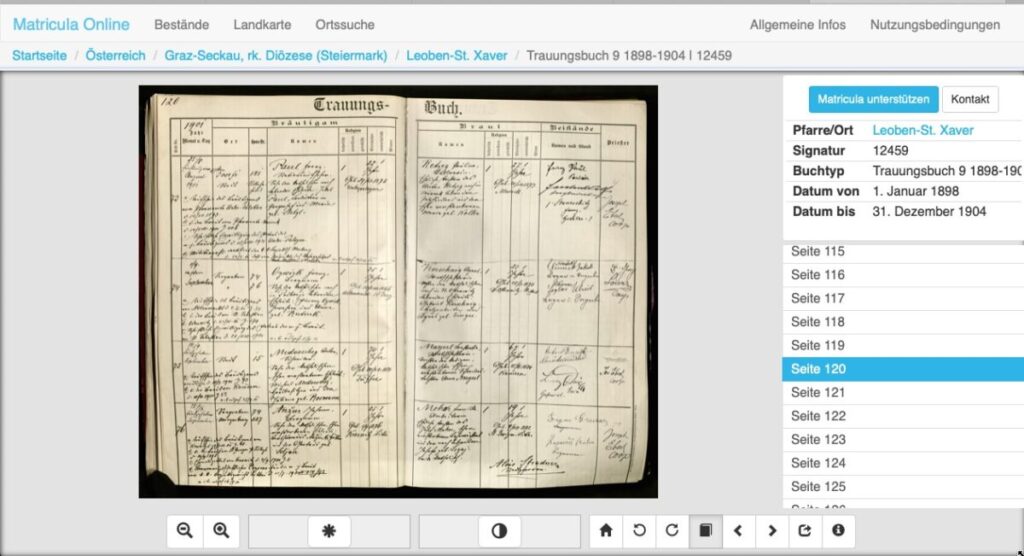

This bottom entry on this page from the Matricula online record books shows that my Slovenian grandparents were married in Leoben, Austria, where he was working as a miner. That is why the record was in Austria, not their home parish church in Slovenia. Thank you, Facebook group!

Even if you know the country, town and the parish your family came from, it might not be enough. Not all of the books were indexed, so you might need to search by scanning each page for the relevant address or last name. Even if you can locate the correct pages, you still need to decipher the handwriting and the language. You can post a link to the relevant page and ask for help from the Facebook group or request the records from the archive.

Requesting Records Search: You can email the archives in English and order records to be sent to you. The Ljubljana archive charges at the rate of 25 Euros per hour for the time needed to search for a record and 7 Euros for a copy of it. The transcribed copy (shown above) will probably be much easier to read than the original cursive handwriting.

The archives accept only cash payments, so you can pay a bank transfer fee or arrange to pick up the document and pay in person if you are planning to visit Slovenia or know someone who can pick it up for you. The archive works cooperatively with the Slovenian Genealogy Society International, another helpful group of expert researchers. Keep in mind that only parish records that are at least 100 years old are available to the public.

What’s NOT so helpful? Old family photographs. Yes, those prized antique images mean nothing to archivists unless you also know the birth/baptism date and location. Once you have the information, your treasured photos will enable you to put faces on the names and relationships.

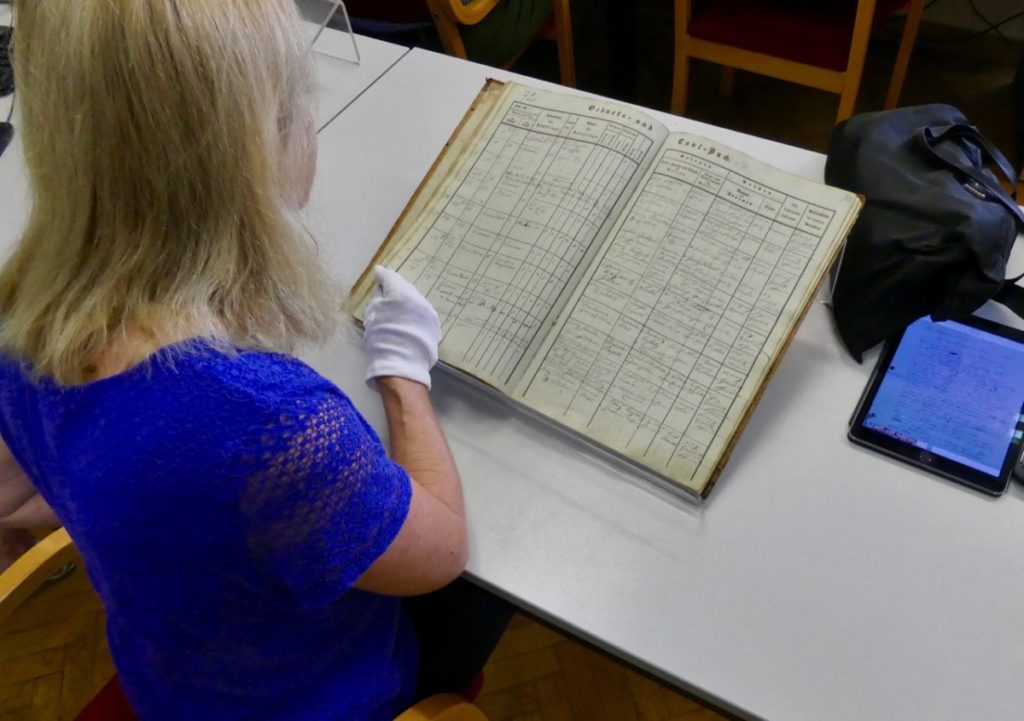

Visiting the Archdiocese Archive in Ljubljana

The availability of online records means you probably don’t need to spend precious minutes of your trip to Slovenia visiting the archdiocesan archives. However, they do have books that are not yet online. The archive’s website says that you must make an appointment well in advance by phone or email. The tiny research room can only hold about a dozen people at one time. Local residents have waited weeks or months for an appointment. Don’t even think about going to the archives unless you already know the town, parish and approximate dates you would like to research. Updates on opening hours and other information are posted on the Ljubljana Archive’s Facebook page, and you can click on a translation into English.

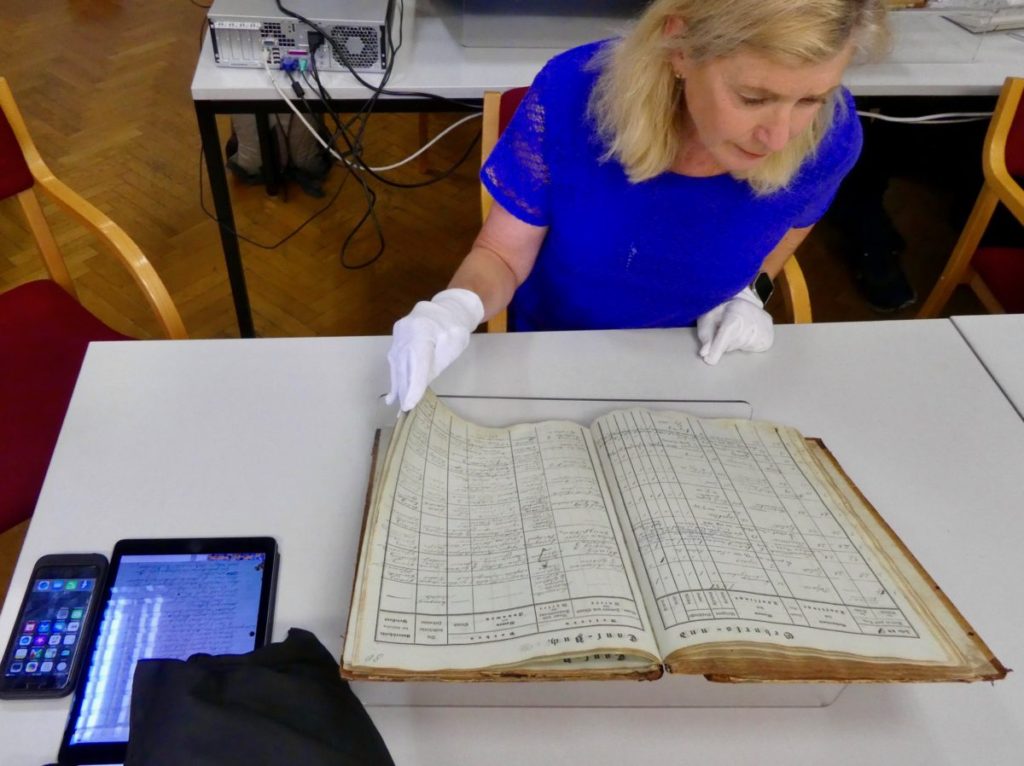

I came here in 2018 in search of my grandmother’s birth record, which was mysteriously missing from the book for St. Benedict’s Parish in her hometown of Kresnice. At the appointed time, I walked to the building on Krekov Trg, at the edge of Ljubljana’s pedestrian zone. Across the street is the famous Puppet Theater and a row of charming cafes. I fortified myself with a cup of coffee.

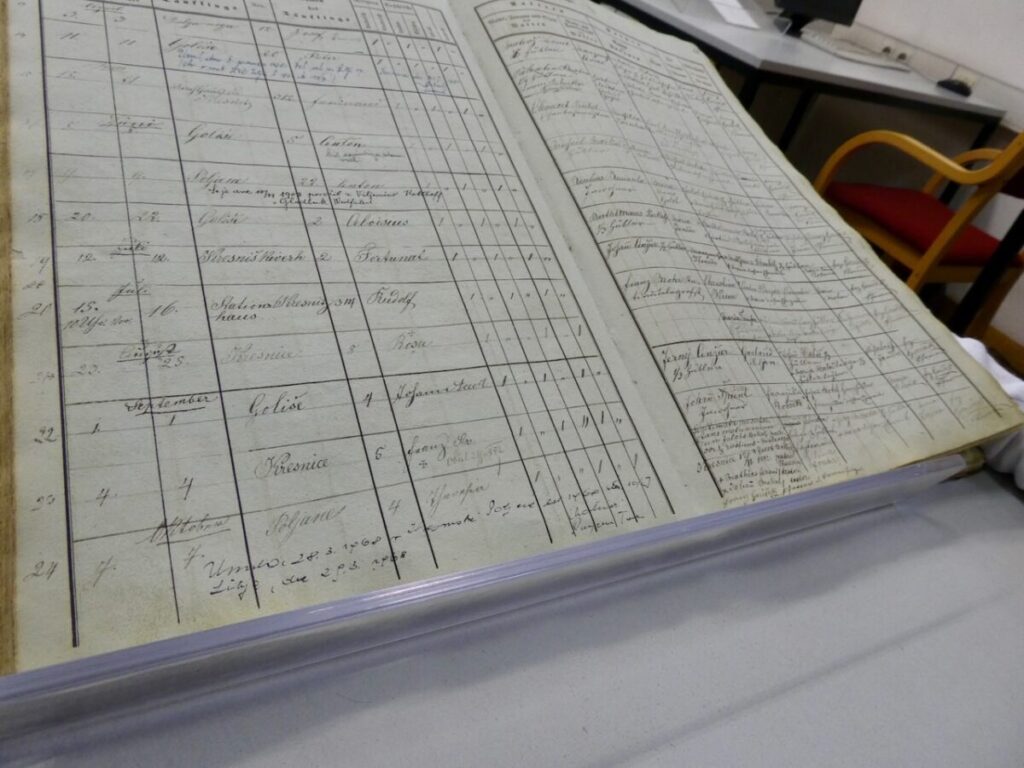

The records in the archive of the Ljubljana archdiocese offer a fascinating glimpse into the lives of your Slovene ancestors, but the cursive handwriting and can be difficult to decipher.

Once inside the research room, I put on the white cloth gloves and began to turn the fragile pages of history. While it was a cool experience, it wasn’t too helpful in terms of finding the missing branches of my Slovenian family tree. As I struggled to read the archaic handwriting, I was left frustrated, with more questions than answers.

On my grandmother’s Mohar side, I now knew she had a brother and a sister who also went to America. The youngest brother, my great uncle Anton, stayed behind to look after their mom, whose maiden name was Josefa Logaj. But there were more possible siblings I’d never heard of, born to a Mohar man and a Logaj wife at a slightly different address in Kresnice. But the parents’ first names were different and –in the pre-birth control times when couples could expect a baby every two years — the kids were born too close together! Was the priest just a sloppy record-keeper in a tiny village where everyone knew everyone else?

On my grandfather’s Anžur side, I suspected he had several sisters who stayed in Slovenia because of some old photographs that were marked “Pop’s sister.” I paged through the records for anyone else born at “Golišče 4” and found that my paternal great-grandparents, Jernej Anžur and Gertrud Seljan, also had daughters named Alojzija and Terezija. What happened to them? Were there other siblings? Could any of their children or grandchildren still be alive in Slovenia or somewhere else?

You may have a similar experience scanning through the pages online. Once again, I turned to the Facebook group for answers. In about 30 seconds after my inquiry, they turned up my grandparents’ marriage record in Leoben, Austria, where Johann had found work in a coal mine. My father’s two oldest brothers, John and Gus, were born there. The marriage record also explained why Frančiška’s baptism record wasn’t in Kresnice; her father worked for the railroad and the family moved around. My grandmother was born in Šentjur, a town with a proud history as a center of railroad transportation.

The archives of the Archdiocese of Ljubljana are in this building on Krekov Trg, near the Farmers’ Market and Dragon Bridge and close to the base of the gondola to Ljubljana castle.

A Lucky Break in My Genealogy Research

To find out more about my extended family tree, I still needed to pay a visit to the records kept at St. Benedict’s parish in Kresnice. This is where the good luck comes in! One of the amazing volunteers on Facebook turned out to be an expert on the history and genealogy of the Sava River valley near Litija, the small towns where my Slovene ancestors were from. Even better — Alenka and her partner were connected to me through the “Logaj” family on my grandmother’s side. She told me there were two Mohar brothers who married Logaj sisters, hence the two sets of neighbors with similar names. She also invited my son and me to be her guest for several tours of the area around Kresnice. But that’s a story for another post!

Want to read more? Find out how I met some of the fascinating Slovenians who share my last name, including a self-proclaimed Slavic knight who lives on the grounds of a ruined castle. Click on this link to “Finding Family Roots in Slovenia.”

Time Travel to Antwerp Belgium in my post on the train station and port where my family departed for the New World, and what you can learn about the ships of the Red Star Line.

And, of course, I recommend downloading the books by my son Andrew Anzur Clement, the Slovenian-American author who lives and writes in Ljubljana.

Finally, if you’re hungry for Slovenian food like grandma used to make, you can order the Cook Eat Slovenia cookbook. It’s in English and has measurements in American units, and they ship to the USA.

If you’re planning a trip to Slovenia, here are my top tips on documents, airfares, hotels, transportation, language, money and more! thanks for clicking here to find a hotel near the Ljubljana archive. You can also search for places to stay elsewhere in Slovenia near your ancestors’ home town. Save money by clicking on the ads alongside this post to see the airfares on CheapoAir or rent a car on Auto Europe before you leave the USA. The referrals support my blog at no cost to you.

Want more posts about life and roots in Slovenia? Like @strangersinthelivingroom on Facebook, and sign up for the occasional email when there is a new post. Subscribe to my YouTube channel for fun travel videos. Follow me on Trip Advisor @strangersblog. Pinning this post? Get more travel ideas from Strangers in the Living Room on Pinterest.